Table of Contents

- 2025 State of Civil Society Report

- Overview +

- Conflict: might replaces right +

- Democracy: regression and resilience +

- Economy: the era of precarity and inequality +

- Climate and environment: heading in the wrong direction +

- Technology: human perils of digital power +

- Gender rights: backlash, resistance and persistence +

- Migrants’ rights: humanity versus hostility +

- United Nations: global governance in crisis +

- Civil society: the struggle continues +

- Acknowledgements +

- Download Report +

- Nowhere near enough funding is being allocated to transform climate and environment commitments into tangible action.

- Civil society is securing climate and environmental victories through multifaceted approaches, including strategic litigation that establishes legal precedents for climate action.

- Environmental defenders face increasing dangers worldwide, ranging from the criminalisation of peaceful protest to arbitrary detention and violence.

As the rich get richer and fossil fuel profits soar, the world burns. On top of fossil fuel companies’ Russian windfall, over the past five decades the oil and gas sector has made profits averaging US$2.8 billion a day. Yet companies are currently scaling back their investments in renewable energies and planning still more extraction – all while using their deep pockets to lobby against measures to rein them in.

Largely as a result of the fossil-fuel powered economic model, 2024 was the hottest year on record and the first year that temperatures exceeded 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels, the limit set by the 2015 Paris Agreement to prevent the worst impacts of climate change. The year was crammed with extreme weather events, from heatwaves to floods. From climate-induced inflation to growing migration, the impacts are being felt in everyday life.

But too little is being done. Fossil fuel companies continue their deadly trade. Global north governments, historically the largest greenhouse gas emitters, are watering down plans as right-wing politicians who typically oppose climate action gain sway, and they’re failing to provide the money needed to help global south countries adjust. International commitments such as the Paris Agreement and the Convention on Biological Diversity show ambition on paper, but not enough is being achieved when states come together at summits such as COP29 climate conference. Progress on new international agreements – such as on plastics – is lacking.

Civil society is doing all it can to demand climate and environmental action that matches the scale of the crisis, winning victories through a combination of tactics including street protest, advocacy and litigation, but it’s coming under attack, with peaceful protesters jailed and activists facing violence in many countries.

For the global-level processes ostensibly designed to protect the climate and biodiversity, 2024 was a letdown. December saw COP29, the latest climate summit and the first to focus on financing. As a matter of both practicality and justice, global south countries want the most powerful economies, which have benefited from the industries that have caused the bulk of climate change, to help finance the costs of a low-carbon transition – as an alternative to pursuing fossil-fuel powered development – and of adapting to climate impacts. An estimated US$1.3 trillion a year is needed, but the most global north states agreed to was US$3 billion a year. This threatens to do little to cap temperature rises and leave the countries that have done the least to cause climate change the most vulnerable.

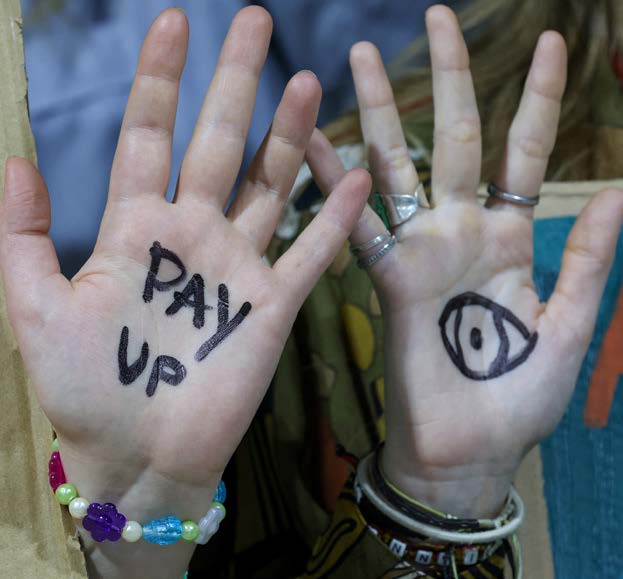

Young activists protest during the COP29 climate change summit in Baku, Azerbaijan, 22 November 2024. Photo by Murad Sezer/Reuters via Gallo Images.

For the second year running, the summit was held in a petrostate, Azerbaijan, and for the third year in a row it was held in a country with closed civic space. Ahead of the summit the government, which systematically suppresses civil society, intensified its crackdown. Treating the meeting as a public relations exercise, it failed to show strong leadership, allowing powerful states’ interests to dominate. This led to the inadequate financing offer and, thanks to repressive petrostates such as Saudi Arabia, no progress on phasing out fossil fuels. With civil society voices subdued and at least 1,773 fossil fuel lobbyists present, failure was pretty much guaranteed.

Meanwhile, a second global summit failed to live up to civil society’s hopes. COP16 on the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, hosted by Colombia in October, also focused on finance. It was supposed to reach a deal to finance the Global Biodiversity Framework, agreed in 2022, which makes a landmark commitment to conserve 30 per cent of land and sea by 2030. But the meeting broke up with no agreement. Global north countries refused to set up a new fund to help meet the US$30 billion commitment. The issue was kicked down the road to meetings scheduled for this year. Meanwhile, more than half of countries have made no plans to meet the biodiversity framework’s targets.

COP16 did make some progress on other fronts. It struck an agreement on biological genetic data, much of which comes from global south countries and is increasingly used by businesses. Under the deal, companies should pay into a new fund when they use the data – but it’s only a voluntary arrangement.

COP16 also broke new ground by setting up a body to represent Indigenous peoples and local communities in negotiations, an innovation other international processes should be encouraged to imitate. This new body could help offset the influence of the business lobby: 1,261 private sector representatives attended COP16 to try to influence its proceedings, including many from fossil fuel companies.

It’s also been a frustrating experience for civil society in negotiations to develop a legally binding treaty on plastic pollution. A fifth round of talks took place in Busan, South Korea but broke up in December without any agreement, even though a treaty was supposed to be finalised by then.

The key division is between states pushing for an ambitious treaty and those – typically oil and gas economies – seeking to limit its scope. Civil society and states that want a strong treaty recognise the devastating impacts of plastic pollution and the need to reduce plastic production; those that want a weak treaty focus solely on waste management, despite the limited effectiveness of recycling.

Plastics are made from chemicals derived from fossil fuels, and the oil and gas industry, while fighting tooth and nail against climate action, sees plastics as a fallback. Once again the sector was well represented, with a record 220 petrochemical industry representatives registered, including several as part of state delegations.

Civil society provides a vital counterweight to industry voices and has maintained a constant presence, combining scientific research, public awareness campaigning, direct action and strategic policy advocacy. For civil society, a bad and rushed deal has been avoided, and the push for a strong treaty remains on.

Beyond international summits, civil society keeps working on all fronts. In April, it won a landmark victory at the European Court of Human Rights, setting a precedent for 46 European states. KlimaSeniorinnen Schweiz won its case against the Swiss government, arguing that their rights to family life and privacy are being violated because the government isn’t doing enough to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Civil society is also taking legal action to protect biodiversity and combat environmental degradation. In Italy in April, civil society won a court case over pollution caused by intensive hazelnut production that makes water undrinkable. This was the third in a series of successful legal challenges.

Activists protest against the East African Crude Oil Pipeline Project in Kampala, Uganda, 26 August 2024. Photo by Badru Katumba/AFP via Getty Images.

ClientEarth, the lead organisation in the recent Italian cases, is also leading a legal challenge against a huge new plastics plant in Belgium. It’s working with 15 other organisations to try to stop chemicals giant Ineos constructing the facility in Antwerp. The action has already led INEOS to scale back its plans.

Historically most climate and environmental litigation has taken place in global north countries. But it’s a growing tactic for civil society in the global south, with climate lawsuits now filed in 55 countries. In August, South Korea’s Constitutional Court ruled that the lack of emissions cuts targets violates the constitutional rights of young people and ordered the government to amend the law. In April, India’s Supreme Court ruled that people have a fundamental right to be free from the harmful impacts of climate change. Another groundbreaking judgment came in Ecuador in July, when a court recognised the rights of the Machángara River, based on the constitution’s recognition of the rights of nature, and ordered the authorities to clean it up.

Advocacy is also achieving some important results. In October, climate activists in the DRC successfully campaigned for the suspension of a controversial oil and gas licence auction that threatened two vital carbon reservoirs. Now they’re pushing for the permanent cancellation of auctions.

Activists are targeting institutions complicit in greenwashing, which through sponsorship arrangements and partnerships lend their credibility and positive public image to businesses that do climate and environmental harm. In July, the UK’s Science Museum agreed to end its sponsorship deal with Norway’s state-owned oil giant Equinor. The decision marked the successful conclusion of an eight-year campaign. Thanks to civil society’s efforts, almost all of the UK’s major cultural institutions that used to accept fossil fuel sponsorship have stopped doing so.

Protest remains another important way of keeping up the pressure for climate action. But in many countries, what authorities once accepted as legitimate protest is being criminalised. Amid a global landscape of civic space restriction, climate activists, and defenders of environmental, land and Indigenous rights, are among the groups most targeted for repression.

Activists for environmental, land and Indigenous rights risk violence, including lethal violence. Global Witness reports that in 2023, 196 people were killed for defending environmental, land and Indigenous rights. Colombia was the most dangerous country with 79 killings, around half of them of Indigenous activists. States and companies often see Indigenous people as an obstacle to extraction and exploitation. Violence and killings often involve criminal groups linked to corporate interests. Of over 2,000 environmental and land rights defenders killed since 2012, around a third were Indigenous people. As well as Colombia, threat levels are high in countries including Brazil, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru.

Mourners attend the funeral of environmental leader Juan López, shot dead for his anti-mining activism, in Tocoa, Honduras, 16 September 2024. Photo by Orlando Sierra/AFP via Getty Images.

Security force violence and mass arrests and detentions, particularly levelled against protesters, are also becoming normalised. In the Netherlands, authorities detained thousands of people for taking part in mass roadblock protests demanding the government keep its promise of ending fossil fuel subsidies. In France, police used violence including stun grenades at a protest against road construction in June and banned another protest in August. In Australia, activists opposing a huge coal terminal development and a gas project were among those arrested in 2024.

In Uganda, campaigners against a major oil development, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, continue to face state repression. In May and June, authorities arbitrarily arrested 11 activists involved in the campaign. They have faced intimidation and pressure to stop their activism.

Activists from Cambodia’s Mother Nature group have paid a heavy price for their work in trying to stand up to powerful economic and political interests seeking to exploit the environment. In July, 10 young activists from the group were given long jail sentences after documenting river pollution.

Serbia’s increasingly authoritarian government has responded to protests against lithium mining with repression. Lithium is used in electric vehicle batteries, but its extraction is highly polluting. Civil society won a victory in stopping licensing in 2022, but the decision was reversed in 2024. Protesters against plans to resume mining have been vilified by the president and jailed for blocking railway lines.

Some states, like the UK, have recently rewritten protest laws to expand the range of offences, increase sentences and strengthen police powers. In July, five Just Stop Oil activists were handed brutally long sentences of up to five years merely for planning a roadblock protest. The UK now arrests environmental protesters at three times the global average rate.

Italy’s right-wing government is introducing new restrictions. In January, parliament passed a law on what it calls ‘eco-vandals’ in response to high-profile awareness-raising stunts at monuments and cultural sites. People could now receive jail terms of up to five years. Another repressive law is being introduced that will allow sentences of up to two years for roadblock protests.

In difficult conditions, change remains possible. Every fraction of a degree that temperature rises can be limited to matters for the lives of millions of people. 2024 delivered some important achievements. In September, for example, the UK shut down its last coal-fired power station; just a decade earlier, around 30 per cent of the UK’s electricity came from coal. This was a testament to the power of long-running civil society advocacy.

In the EU, a breakthrough came in July with the adoption of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. This aims to protect human rights and the environment while responding to climate change, requiring large companies to align with the Paris Agreement. European courts will have new powers to hold companies to account, with fines for violations. In some cases, civil society groups will be able to bring claims against companies.

Civil society played a major role in campaigning for the directive, working with the EU presidency and supportive states and engaging with large companies to encourage their support, in the face of opposition from right-wing parties. Some compromises had to be made to get the deal through, with the final directive focusing on a smaller number of companies. And now the rightward shift and loss of seats for green parties in the European Parliament may mean less urgency. It falls to civil society to keep up the pressure and scrutinise companies over their compliance.

Another landmark came in May, when the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea issued its first climate-related ruling, stating that greenhouse gases absorbed by oceans count as marine pollution. This means states are expected to control and reduce emissions. The court’s opinion sets an important precedent in establishing that states have obligations beyond the Paris Agreement.

The ruling could help inform other international processes seeking to raise the bar on states’ responsibilities. In December, the ICJ began hearing a case brought by a group of Pacific Island states. They’re seeking an advisory opinion on what states are required to do to address climate change and help countries suffering its worst impacts. The origins of the case lie in civil society: in 2019, student groups in eight countries formed the Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change network to urge their national leaders to take the issue to the court. The court has now heard submissions from over 100 states and organisations. A positive ruling could create a powerful new norm that civil society can use to hold states to account.

Similar action is underway at the regional level. In 2023, Chile and Colombia asked the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for an advisory opinion on their duties and obligations to protect human rights in the face of the climate crisis. Public hearings took place in 2024, reflecting the high level of interest, with over 220 civil society groups making submissions. The court is expected to issue its opinion in 2025.

There’s a rocky road ahead, given the implications of Trump’s return. The world’s biggest historical emitter and largest current fossil fuel extractor has once again given notice of its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, torn up renewable energy policies and made it easier to drill for fossil fuels. In response, other industrialised nations must show climate leadership. US subnational administrations under more progressive control must do all they can to curb emissions.

Even then, radical change is needed on funding. It may be hard to reach international agreements on climate and the environment, but it’s clearly even harder to finance them. Ambition is needed in 2025. The figures involved may seem huge, but in global terms they’re tiny. The US$1.3 trillion needed for climate action is less than one per cent of global GDP, and far less than military spending. It’s also much less than the cost will be of dealing with the damage caused by unabated climate change.

To drive more ambitious commitments and follow-up, it’s also necessary to reform summit processes so states genuinely committed to climate action host and lead, civil society is able to participate fully and fossil fuel lobbyists are excluded. Civil society will be pushing for improvements at COP30 in Brazil this November.

Ahead of COP30, states are required to submit new plans – nationally determined contributions – to cut greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change. This is probably the last chance to keep the temperature rise below 1.5 degrees. Civil society is pushing for these plans to show the ambition needed – and for money to be mobilised at the scale required.

Without civil society pressure, there’ll be no progress. States and companies must stop attacking climate and environmental activists and organisations. They must let civil society play its leading role in responding to the crisis.