Table of Contents

- 2025 State of Civil Society Report

- Overview +

- Conflict: might replaces right +

- Democracy: regression and resilience +

- Economy: the era of precarity and inequality +

- Climate and environment: heading in the wrong direction +

- Technology: human perils of digital power +

- Gender rights: backlash, resistance and persistence +

- Migrants’ rights: humanity versus hostility +

- United Nations: global governance in crisis +

- Civil society: the struggle continues +

- Acknowledgements +

- Download Report +

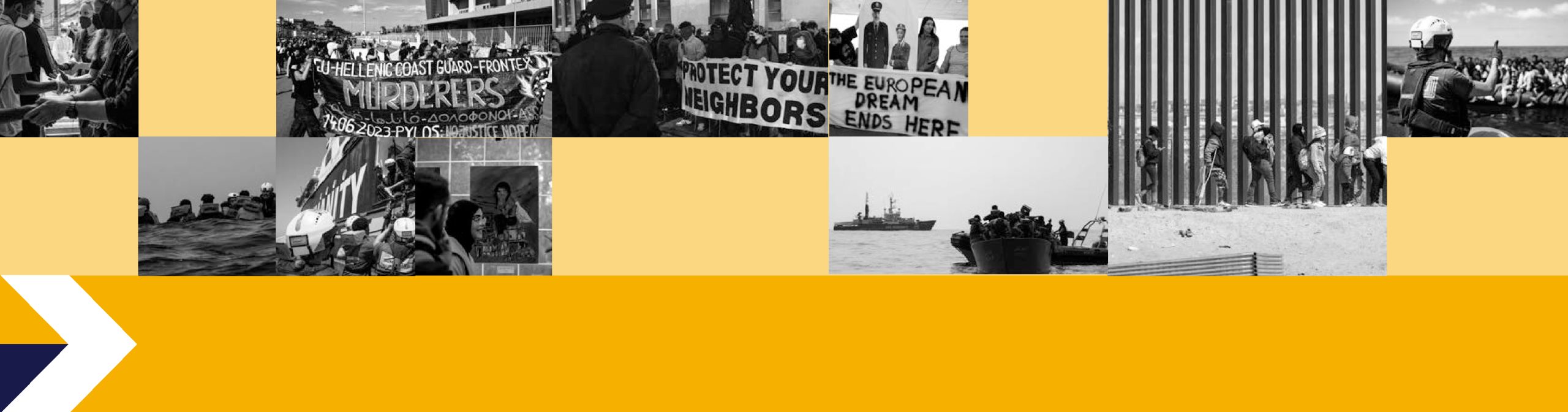

- Global displacement has hit a new record, with most refugees hosted by global south countries.

- Despite receiving a minority of migrants, global north states are adopting increasingly restrictive policies, driven by a rightwards shift.

- Civil society continues defending migrants’ rights despite growing criminalisation of its humanitarian work.

The same regressive forces attacking women’s and LGBTQI+ people’s rights are also targeting migrants and refugees. Here, they’re finding an even more receptive audience among many governments. Worsening political hostility means civil society faces mounting challenges in efforts to protect migrants’ rights. The situation is becoming particularly difficult in two major migration corridors where a concerning trend of prioritising border control over human rights has consolidated: North America and the EU.

Anti-migrant policies deny the reality that more people are on the move than ever before. Each year, with 2024 being no exception, sees a record in the number of migrants and refugees. An estimated 123 million people are now forcibly displaced worldwide, including 75.9 million internally displaced. Sudan’s conflict alone has left almost 11 million people internally displaced, the highest figure ever recorded for a single country. Many others are fleeing to neighbouring Chad and South Sudan, which are grappling with their own humanitarian crises.

People wait to surrender to US authorities after crossing the Río Grande from Mexico, 7 March 2024. Photo by David Peinado/Anadolu via Getty Images.

Millions have fled Ukraine, while over two million have been internally displaced in the DRC, along with a similar number in Gaza and Lebanon. In the Americas, one of the largest modern migratory movements continues unabated, with an estimated eight million Venezuelans having fled since 2015, the largest recorded forced displacement not caused by war.

The ongoing surge in migration is driven by a complex interplay of factors including conflict, political persecution, human rights violations, economic strife and climate disasters. But the political backlash that mobilises against people forced on the move generally doesn’t address the causes.

Current frameworks for understanding migration, particularly the artificial distinction between voluntary migration and forced displacement, are increasingly inadequate. They fail to understand the complex realities of movement, where economic necessity can be as coercive as direct persecution. Reality also disproves prejudice: contrary to what the backlash suggests, most migration occurs between global south countries, rather than from global south to north. At least 71 per cent of the world’s international refugees are hosted in global south countries and 69 per cent stay in countries that neighbour their own.

Migration policies have become increasingly restrictive in the USA. During the first Trump administration, the USA pursued a deterrence policy, marked by the propagandised construction of about 130 kilometres worth of new barriers on the US-Mexico border, the separation of families and the implementation of the Remain in Mexico policy, which forced asylum seekers to await their US immigration court hearings in Mexico. Human rights organisations widely condemned these policies. The Biden administration pursued a mix of humanitarian and restrictive measures: it rolled back some of its predecessor’s restrictive measures but implemented stricter asylum rules and expanded Title 42 expulsions, a policy initially introduced during the pandemic to rapidly expel migrants at the border.

The US Border Patrol reported over 2.1 million encounters at the border with Mexico during the 2024 fiscal year, down from 2.5 million in 2023. This was attributed to a new approach that combined restricting asylum eligibility for those who crossed the border without permission and expanding legal migration pathways. But this changed on day one of the second Trump administration, with a succession of executive orders declaring a ‘national emergency’ at the southern border, enabling military deployment, cancelling the mobile app used to process applications, suspending all entries by declaring an ‘invasion’ and dissolving the family reunification taskforce that was still working to reunite families separated by the first Trump administration.

Protesters march to protest against raids targeting migrants in New York, USA, 13 February 2025. Photo by Mostafa Bassim/Anadolu via Getty Images.

Inauguration Day orders instructed immigration authorities to detain people ‘to the fullest extent permitted by law’, and immigration raids started soon afterwards, promising the largest deportation programme in US history. The new approach, conflating illegal immigration with criminality and using rhetoric about invasion reminiscent of the ‘great replacement’ conspiracy theory, raised serious concerns about the potential for increased violence against migrants.

In Europe, the rise of right-wing populist politics has led to the prioritisation of border control over human rights. A February 2025 gathering of far-right European leaders in Madrid underscored the growing trend of anti-immigration sentiment. Representing the Patriots for Europe group, which holds 86 seats in the European Parliament, far-right leaders including France’s Marine Le Pen, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Spain’s Santiago Abascal explicitly positioned themselves against what they call ‘open door immigration policies’. They claim immigration destabilises nations and threatens European identity and culture. This coalition amassed over 19 million votes in the European Parliament elections.

Even as the number of people entering the EU was falling, the European Commission’s response to mounting political pressure was to develop the EU Migration Pact, a comprehensive legislative package aimed at facilitating deportations and allowing member states to close their borders on security grounds. The EU’s approach has increasingly prioritised deterrence and externalised border control in states outside Europe, as evidenced by controversial deals with the authoritarian governments of Egypt and Tunisia, through which the EU provides substantial funding in exchange for heightened measures to stop migrants crossing into Europe. Thes agreements mirror that struck with Turkey in 2016, which enabled further human rights abuses. The result is avoidable deaths at the EU’s borders and an undermining of the EU’s claims to stand as a champion of human rights and civil society ally.

Activists protest against the Italy-Albania migrant processing agreement as asylum seekers arrive on an Italian navy vessel in Shëngjin, Albania, 16 October 2024. Photo by Florion Goga/Reuters via Gallo Images.

In 2024, some EU states echoed the policy pioneered by the UK, where the former government tried to remove asylum seekers to Rwanda for processing. The new government at least scrapped this plan, although the arguments it made were about cost and efficiency and there’s been no let-up in hostile rhetoric.

Italy’s right-wing government agreed to outsource the management of asylum and return procedures to Albania, allowing for the transfer of migrants rescued by Italian vessels in international waters to new Albanian detention centres, funded and administered by Italy. The policy was intended to act as a deterrent, and although it was initially blocked by civil society court action, it eventually resumed. However, the detention centres are currently empty following a further court ruling that ordered the government to return the people held there to Italy. Despite the scheme’s problems, Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is increasingly seen as an influential figure in the EU, and the European Commission is backing Italy’s position in a European Court of Justice case to decide on the policy’s legality.

Another outsourcing plan has been put forward in the Netherlands, with the Party for Freedom proposing to send rejected asylum seekers to Uganda in exchange for financial aid. Rights groups reject this abdication of the state’s protection obligations, highlighting Uganda’s problematic human rights record and anti-LGBTQI+ laws.

Germany changed its Schengen area passport-free policy, implementing expanded border controls. Civil society groups warn that these supposedly temporary measures could become permanent, potentially influencing other European countries to follow suit. The policy changes reflect the far right’s growing profile, which has led several German states to push for increasingly stringent measures, including tougher deportation rules, reduced social benefits, tighter restrictions on family reunification and expanded powers for immigration enforcement.

In many of 2024’s elections, politicians cynically instrumentalised migration concerns and deliberately stoked tensions. Migration was a battleground in several campaigns, with parties on the right and, increasingly, in the centre taking hard-line stances.

This instrumentalisation often involved the use of misleading or false information about migrants, exaggerating the scale of immigration and linking migrants to crime and other social ills, rhetoric that dehumanises migrants and fosters a climate of fear and hostility.

Migration was a dominant issue in the run-up to the UK’s July election. The incumbent Conservative government faced sustained pressure over the number of irregular crossings of the English Channel. The Labour party, which won power, adopted a more aggressive tone, while the right-wing populist Reform UK party has made migration its core issue and now leads some polls. The ideological spectrum has shifted rightwards on immigration.

In the European Parliament elections, far-right parties running on explicitly anti-immigration platforms made significant gains. These included the National Rally’s significant victory in France, the AfD’s best-ever performance in Germany and the 28 per cent received by Meloni’s Brothers of Italy. Bucking the trend, far-right parties with anti-immigration stances underperformed in Nordic countries, where they’d been on the rise only a few years earlier. They were surpassed by parties on the left, in part because far-right parties had already played a role in government in some countries and some voters were disenchanted with them.

Protesters gather in Brighton, UK, to show solidarity with migrants and refugees at a counter-protest in response to anti-immigration rallies, 8 August 2024. Photo by Toby Melville/Reuters via Gallo Images.

The increased representation of far-right parties in the European Parliament is likely to have a significant impact on EU migration policy as they push for stricter border controls, reduced immigration levels and a greater emphasis on narrow national sovereignty.

Immigration was of course one of the most contentious and defining issues in the 2024 US presidential election, with the US-Mexico border question drawing intense focus from both major parties and intersecting with other major campaign themes, including public safety, economic policy and national security. Trump’s victory suggests he won the argument on this. Civil society warned throughout that the politicisation of migration would only lead to more suffering and death among those attempting to cross into the USA.

The politicisation of migration isn’t confined to the global north, as the use of populist anti-migrant rhetoric ahead of Tunisia’s election indicates. In the Dominican Republic, Haitian migration was also a key issue in the May presidential election campaign, with most candidates seeking political gain by exploiting racist prejudice in Dominican society. In doing so, they further legitimised the systematic violation of the rights of Haitian migrants and their descendants born in the Dominican Republic, many of whom are denied citizenship. In India, in the run-up to the Delhi Legislative Assembly election in February 2025, the two major parties in the assembly competed over which could position themselves as more hostile towards Bangladeshi migrants.

Civil society is doing vital work protecting migrants’ rights amid rising political hostility and increasingly restrictive policies. Its work spans search-and-rescue operations at sea, provision of humanitarian assistance, documentation of rights violations, support for integration into host communities, advocacy for policy change and education and awareness-raising efforts to counter xenophobia and discrimination. However, activists and organisations that help migrants and refugees increasingly face legal repercussions.

The criminalisation of solidarity is particularly evident in southern Europe. Humanitarian groups carrying out search-and-rescue missions in the Mediterranean, where over 2,200 migrants drowned in 2024, face significant pushback from governments that view their actions as undermining border control efforts.

In 2023, Italy made it illegal for search-and-rescue organisations to conduct more than one rescue per trip, imposing heavy fines and boat seizures for noncompliance. Italian authorities routinely send rescue vessels to distant ports, forcing them to travel long distances to disembark survivors, and issue detention orders based on questionable allegations of maritime safety violations. For instance, in August, they issued a 60-day detention order on the Doctors Without Borders vessel Geo Barents for supposedly endangering lives, based on information from the Libyan Coast Guard. In December, SOS Méditerranée was forced to travel over 1,600 kilometres to bring 162 survivors to safety after authorities ignored pleas for a closer port. These actions achieved their intended goal of reducing active rescue ships, leading to an increase in deaths.

In December the European Council developed a text to be considered by the European Parliament on new EU rules about migrant smuggling. Critics argue these could further criminalise migrants and those acting in solidarity with them.

The challenges extend beyond Europe. As part of the politicised hostility in Tunisia, those campaigning for the rights of Black African migrants face increasing criminalisation, with President Saied labelling them as ‘traitors’ and ‘mercenaries’ who receive foreign funding to help migrants settle. These accusations often lead to criminal charges, prosecution and arrests.

Despite the growing obstacles, civil society maintains its commitment to protecting migrants’ and refugees’ human rights. While acknowledging the economic and social anxieties that right-wing populists exploit, activists advocate for domestic social policy solutions that respect human rights and international cooperation aimed at addressing migration’s root causes rather than punishing migrants. They emphasise the need to shift away from fear-based policies toward comprehensive solutions that uphold human dignity while addressing the complex drivers that put people on the move.