Table of Contents

- 2025 State of Civil Society Report

- Overview +

- Conflict: might replaces right +

- Democracy: regression and resilience +

- Economy: the era of precarity and inequality +

- Climate and environment: heading in the wrong direction +

- Technology: human perils of digital power +

- Gender rights: backlash, resistance and persistence +

- Migrants’ rights: humanity versus hostility +

- United Nations: global governance in crisis +

- Civil society: the struggle continues +

- Acknowledgements +

- Download Report +

- International laws are being routinely violated in conflicts, with civilians deliberately targeted and war crimes committed with impunity.

- Women and children bear the heaviest burdens in conflict zones, and women-led organisations play a crucial but unrecognised role in humanitarian response and peacebuilding.

- Civil society is working to stop arms transfers to perpetrators of human rights abuses, ensure accountability for rights violations and build coalitions for peace despite growing restrictions on its work.

Conflict scars the world. At the time of publication, a fragile and far from fully respected ceasefire holds in Gaza and a cessation of hostilities may happen in Ukraine under pressure from the Trump administration, rewarding Russia’s imperial ambitions and sacrificing Ukraine’s sovereignty in the process. But conflicts continue to rage off the international radar in several countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Myanmar and Sudan. The consequences are death and destruction on an unimaginable scale, mass displacement and enduring trauma.

In all these conflicts civilians are being killed, not by accident but due to deliberate targeting. Civil society personnel, humanitarian workers and journalists are being killed for their work helping civilians, defending rights and documenting abuses. Long-established principles of international humanitarian law meant to provide protection and minimise human suffering are being flouted with impunity. United Nations (UN) institutions and other international bodies appear powerless. The principle that might makes right is winning out over international law.

Nowhere has the devastation been greater than in Gaza. So far at least 48,291 people have been killed in Israel’s attacks, most of them civilians, and this figure may well be an underestimate. At least 1.9 million people, 90 per cent of the population, have been displaced, with 92 per cent of Gaza’s homes destroyed or severely damaged. Some 170 journalists and at least 320 humanitarian workers have been killed, many deliberately targeted. The trauma will be felt for generations. The consequences of the genocidal decisions made by Israel’s leaders are sure to fuel further instability and contribute to a climate of global impunity.

The ceasefire agreed in January 2025, brokered by Egypt, Qatar and the USA, brought a merciful pause in the killing, although with repeated violations, including Israel’s further blocking of humanitarian access. At the time of writing it’s uncertain whether the supposed second and third stages – a permanent ceasefire and reconstruction– will be respected.

The deal Israel eventually accepted was little different from the one Hamas agreed to in May 2024 and put forward in a UN Security Council resolution in June, which Israel ignored. It could have happened much sooner, and with much less killing. But slaughter was a political choice. It was Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s decision to unleash collective punishment – a war crime – on an entire population for the actions of a terrorist group, with no evident attempt to limit impacts on civilians. Unpopular before the 7 October attacks and awaiting corruption trials, Netanyahu faced further public criticism for the failure of Israel’s vast security apparatus. War has held his government together and kept him in power.

The Biden administration provided diplomatic cover and arms to Israel, and now Trump’s return makes a lasting peace less likely. Trump appears to see Gaza’s eventual reconstruction as a property development deal where he can build a second Dubai, with the remaining Gazan population ethnically cleansed through removal to other countries. The idea involves extraordinary doublethink: it simultaneously acknowledges that Gaza’s destruction leaves the territory needing complete reconstruction while rejecting the possibility that such extensive damage might constitute evidence of human rights crimes.

Israel’s violence has extended to the West Bank and its deadly bombing of Lebanon, and it also took advantage of the ousting of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad in December to invade the part of the Golan Heights it didn’t already occupy. In February 2025, it launched another bombing campaign against Syria.

Domestically, Israel’s violence has been accompanied by a sustained crackdown. Since the start of the current phase of conflict, the Israeli government has passed at least 19 emergency regulations restricting key freedoms. Israeli authorities have consistently used violence against protesters and journalists covering protests and subjected Palestinian citizens of Israel to surveillance and arbitrary arrest, including on terrorism charges.

Here, Israel has a lot in common with Russia, where the authoritarian state has imposed a barrage of new restrictions to suppress domestic dissent during its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, while relentlessly propagating a false narrative portraying Russia as victim rather than aggressor and systematically targeting Ukrainian civilians with deadly strikes on residential areas, hospitals and other non-military infrastructure.

Visitors contemplate a painting at an exhibition by Palestinian women artists depicting war suffering in Deir Al-Balah, Gaza, 10 December 2024. Photo by Saeed Jaras/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty Images.

Israel’s restrictions have reverberated around the world. Authorities in at least 12 European countries have banned protests in solidarity with Palestine, and demonstrations in many countries have been met with vilification, violence and arrests. Around 10 per cent of all civic space violations recorded by the CIVICUS Monitor in 2024 were related to Israel, Palestine and solidarity protests around the world.

Students set up protest camps on many US campuses, including to call for divestment from companies with ties to Israel. Many institutions responded by banning encampments, imposing restrictions and suspending students, and students have had job offers withdrawn after taking part. Security forces have used violence against protesters. Protesting students have routinely been vilified as antisemitic.

Artists of all kinds are also working to document the suffering and tell the stories of Gaza. Incredibly, Gazan artists are making art in the midst of devastation, and creative people around the world are speaking out in solidarity, but they’re facing a backlash for doing so. People are being disinvited from events, having contracts cancelled and awards withdrawn, all of which may encourage self-censorship. It’s getting harder for people who speak out against genocide in the media, while social media platforms are censoring voices in solidarity with Palestine even as hate speech flourishes. The right to speak out on Palestine is a key test of respect for freedoms that too many in positions of power are failing.

Most of those killed by Israeli forces in Gaza have been women and children, and it’s sickeningly the case that women and girls pay a devastating price in conflicts the world over. A record number of women and girls – around 612 million are affected by armed conflict.

In Sudan, both sides in the brutal civil war are waging a campaign of systematic sexual violence, including sexual assault, abduction and forced marriage. Child marriage and sexual exploitation and trafficking have increased.

In conflict conditions, women are often the first to go hungry, and girls are denied education much more than boys. Women survivors have little hope that justice systems will hold those who inflicted such cruelty on them to account.

A woman with a Sudanese flag-painted nail holds a placard at a protest outside ceasefire talks in Geneva, Switzerland,14 August 2024. Photo by Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images.

Women aren’t just targets in conflicts – they’re also a vital but under-recognised part of the solution. In Sudan, local women’s organisations are braving dangerous conditions to deliver essential aid, running safe houses, holding clinics in refugee camps and providing survivors with psychosocial support. They’re documenting and exposing human rights abuses and atrocities, leading international advocacy campaigns and demanding accountability.

Women-led organisations should be at the forefront of peace efforts. But women’s voices are often excluded from peacebuilding processes. Evidence shows that peace agreements last longer and are better implemented when women are involved. Yet, as the UN’s annual report on Women, Peace and Security shows, women currently make up only 9.6 per cent of negotiators in peace processes.

Any meaningful effort to build lasting peace requires the substantive involvement of women throughout. In Syria, the change of government following a long civil war presents a crucial opportunity. A key measure of success in Syria will be whether peace processes advance women’s rights.

This threatens to be an age of impunity: perpetrators of conflict are broadly able to evade accountability. Even when ceasefires come and hostilities end, those responsible for mass atrocities are unlikely to face justice.

The body of international humanitarian and human rights law developed in the aftermath of the Second World War was designed to ensure that atrocities of the kind committed by Nazi Germany and its allies would never happen again and, if they did, those responsible would be punished. But international law and the institutions designed to oversee it are being tested by conflicts in which aggressors act with impunity while states make hypocritical calculations based on political alliances rather than legal principles.

The Security Council has been as ineffectual towards Israel as it has with Russia, in both cases because of the veto power of its five permanent members. Russia has prevented any action against its blatant violation of the Council’s mandate, while the USA, as Israel’s chief ally, has consistently blocked condemnation since the start of the bombardment of Gaza. The Security Council has issued a handful of weak resolutions, heavily diluted through diplomatic tussles, which the Israeli government has found easy to ignore. UN General Assembly resolutions have come in the absence of Security Council action, but these lack enforcement mechanisms.

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s main judicial body, at least acted quickly in January 2024 when it issued an urgent interim ruling on a case filed by South Africa alleging Israel is in breach of the Genocide Convention. The judges found there was a plausible risk of genocide and gave Israel six orders, including to ‘take all measures in its power’ to ensure its forces comply with the Genocide Convention, facilitate humanitarian access and stop public incitements to genocide. But Israel simply ignored them, as it did when the court issued further orders in March and May. It did the same in July, when the ICJ issued an advisory opinion in a separate case concluding that Israel’s illegal settlements constitute multiple violations of international law. Netanyahu lashed out at the decision, while the Security Council hasn’t followed up on Israel’s failure to comply with ICJ orders.

Double standards are on ample display. Several global north states that got behind a case The Gambia brought against Myanmar alleging breaches of the Genocide Convention criticised South Africa for initiating the case against Israel.

Then there’s the International Criminal Court (ICC), which prosecutes individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression, operating as a global court of last resort when national justice is absent. In November, it issued arrest warrants against Netanyahu, former Israeli defence minister Yoav Gallant and three Hamas leaders who are now dead. The ICC found reasonable grounds to believe Gallant and Netanyahu were responsible for ‘the war crime of starvation as a method of warfare’ and ‘the crimes against humanity of murder, persecution, and other inhumane acts’.

Any state that’s adopted the Rome Statute to recognise the ICC’s jurisdiction is obliged to arrest Netanyahu if he visits their country. But several global north states said they wouldn’t arrest him or otherwise distanced themselves from the court’s decision. Germany’s likely next chancellor Friedrich Merz has made a point of assuring Netanyahu he can visit the country without arrest. It was a different story in 2023, when the ICC issued arrest warrants against Vladimir Putin and an associate, and just about every global north state lined up to affirm their support and demand justice.

Meanwhile the Israeli state is engaged in a long dirty tricks campaign to try to undermine the ICC, including through hacking, surveillance, smears and threats. Netanyahu reacted to the decision to issue warrants by comparing ICC chief Karim Khan to a Nazi-era judge. One of the early acts of the second Trump administration was to impose sanctions on ICC staff, as it did the first time around.

The ICC has made clear that being a key ally of a global north power doesn’t necessarily guarantee impunity, and the response has been telling. The notion of a rules-based international order can’t be sustained if states pick and choose when they think the rules should apply on the basis of their allegiances.

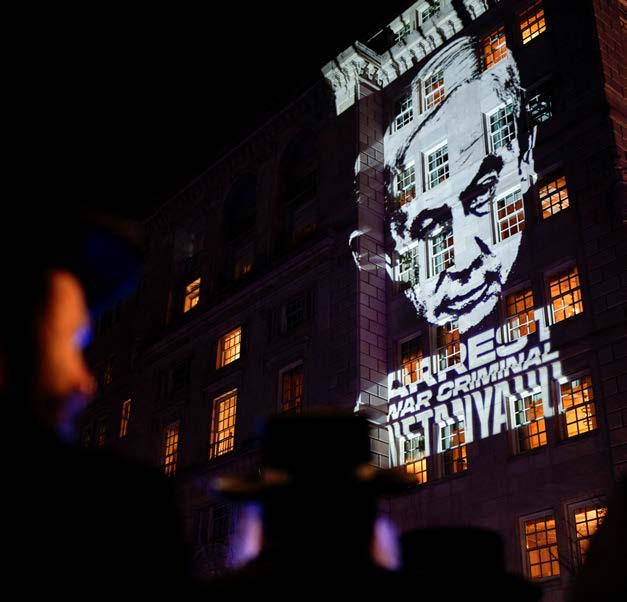

An image of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and a call for his arrest are projected onto a building near the White House as he meets with Donald Trump in Washington DC, USA, 4 February 2025. Photo by Kent Nishimura/Reuters via Gallo Images.

Many global north states have also been only too happy to believe the Israeli government’s smears about UNRWA, the UN’s agency for Palestine, which Israel is determined to shut down. They cancelled or suspended funding based on Israeli claims that turned out to be largely unsubstantiated, causing great harm to people.

This pattern of international dysfunction and naked self-interest can be seen in other conflicts. There’s been over four years of fighting in Myanmar since the 2021 military coup, with forces opposed to the junta now controlling the majority of territory and the military responding with brutal repression. But the key regional body, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, stands on the sidelines, with its authoritarian member states happy to pretend the plan put forward after the coup still has any credibility, ignoring civil society’s alternatives – a recipe for the killing to continue.

State interests and alliances are hampering progress elsewhere. Authoritarian Rwanda is the power behind the rebel forces that captured the DRC city of Goma in January 2025, but many global north states prioritise their diplomatic relations over holding it accountable. Conflict also continues in parts of Ethiopia, but the government has leveraged its relationships to limit international scrutiny, and the African Union and the UN have largely been silent. Civil war rages across Sudan partly because the United Arab Emirates (UAE) heavily backs the militia in its bid to replace the government.

Civil society is calling for everyone to respect international law, for the international system to do its job and for states to put narrow national interests aside. A potentially promising step in this direction comes in the form of a proposed treaty to prevent and punish crimes against humanity. The UN adopted a resolution in December 2024 with the aim of agreeing a final draft by 2029. The treaty would require states to cooperate internationally to protect victims and witnesses and to prosecute or extradite suspects. But it faces some strong opponents, not least Russia, which won concessions on the resolution’s language and timelines before it was adopted.

Civil society has played a key role in advocating for the treaty, urging governments to back it and drafting articles for consideration. International law is an imperfect and always incomplete project, but the only alternative is global anarchy, where the powerful can impose their will without constraint. States that support a treaty on crimes against humanity must work with civil society to defeat attempts to delay and weaken it.

Another way civil society seeks to uphold international law is by advocating for an end to arms transfers to Israel. The Arms Trade Treaty, which came into force in 2014, is designed to prevent arms transfers that could lead to serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. UN human rights experts have called for an immediate halt to all arms exports to Israel on the grounds that they’ll likely be used to violate international humanitarian law. Some states, including Belgium, Canada, Japan and Spain, have suspended shipments, but many others continue to supply Israel.

Civil society in several European countries has gone to court to try to halt supplies, including in Germany, the second-largest arms provider to Israel after the USA, along with Denmark, France, the Netherlands and the UK. A key issue is the supply of parts used in F-35 fighter jets, a major weapon in Israel’s killings of civilians.

In February 2024, a court in the Netherlands ordered the Dutch government to stop the transfer of all such parts, citing clear risks of violations of international humanitarian law. The court also rejected the government’s argument that evidence from civil society shouldn’t be taken seriously. The government however has appealed to the supreme court to try to overturn the ruling.

Sudanese exiles and allies denounce escalating violence and the role of the United Arab Emirates as a supplier of weapons and ammunition to the Rapid Support Forces at a demonstration in London, UK, 21 January 2024. Photo by Mark Kerrison/In Pictures via Getty Images.

In Denmark, the case remains pending, but one notable aspect has been the rapid public support for the action’s crowdfunding appeal. Meanwhile in the UK, following extensive civil society advocacy, the government announced a partial suspension of arms sales to Israel in September. But this only involved the cancellation of around 30 of 350 licences and didn’t include parts supplied to countries assembling F-35s, 15 per cent of which come from the UK. UK law is clear about compliance with the Arms Trade Treaty, and civil society continues to pursue legal action.

More broadly, civil society is working to focus public pressure on the deadly arms trade. Global military spending has risen for nine years running to stand at US$2.3 trillion a year, and the total value of arms imports and exports between states is estimated to be at least US$138 billion. The USA is the largest arms exporter, followed by France, Russia, China and Germany; these five account for three quarters of arms exports.

Arms spending is only likely to increase. The Trump administration is pressuring NATO members to spend more on defence, while current fears from European states that they’ll no longer be able to rely on US defence backing are also likely to drive up expenditure on European defence capabilities. In a sign of the direction of travel, in February 2025 the UK government announced it would increase its defence spending by slashing its foreign aid budget, prioritising arms over support for the world’s most vulnerable people.

There are multiple conflicts, including in Gaza, Myanmar and Sudan, where it’s clear states are supplying weapons that are being used in violation of international law. China, India and Russia, for example, are providing arms to Myanmar’s murderous junta, while the UAE is supplying rebel forces who are killing civilians in Sudan. One problem is that while 116 states have ratified the Arms Trade Treaty, it falls far short of global coverage. Major holdouts include Russia and the USA. Civil society was at the forefront of pushing for the treaty and remains active in trying to strengthen the global rules and subject arms transfers to greater human rights scrutiny.

As technology develops, it’s being used to make killing easier, and it’s developing much faster than regulations. There’s particular concern about the use of AI and automated weapons. AI is being integrated into military systems, including in processes that decide who lives and dies, reducing the potential for the exercise of human conscience. Faulty or biased data can have huge human costs.

Israel uses AI to generate lists of assassination targets, leading to civilian deaths. The military has been accused of expanding its decision of who constitutes a valid target in violation of international law, essentially broadening the number of targets to match its killing capacity. Soldiers are given just seconds to approve or reject a machine-generated assassination recommendation. This represents a further depersonalisation of lethal violence, removing those responsible for killing from the scene, in a way pioneered by remote drone warfare. Developments like these – including the potential use of killer robots – must urgently be the subject of effective international regulation.

The early days of the Trump administration have unleashed a wave of global disruption. Talks about Ukraine were held between Russia and the USA that excluded Ukraine, followed by the ugly and very public televised bullying of Volodymyr Zelenskyy by Trump and his vice president J D Vance. There’s no attempt to hide the naked self-interest and transactional politics behind the US government’s determination to condition any future role in Ukraine on privileged access to minerals. The USA also did something until recently unimaginable, siding with Belarus, North Korea and Russia in voting against a UN General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s invasion. Meanwhile there’s been endless rhetoric about the USA somehow assimilating Canada and Greenland, taking control of the Panama canal and ‘owning’ Gaza.

In this might-makes-right world, little can be ruled out, including a Russia-USA alliance or a carve-up of the world into spheres of influence centred on China, Russia and the USA, underpinned by the ever-present possibility of conflict to assert regional dominance. The lesson Russia may take from its war with Ukraine is that it can intervene militarily elsewhere around its borders, while for China it could be a signal to step up plans to invade Taiwan, something that would destabilise Asia and create insecurity among China’s many other neighbours.

But global realignments can also cause sudden shifts that create opportunities for local breakthroughs. In Syria’s case, the changing dynamics and priorities of Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Russia and Turkey, including as a result of conflicts they’re involved in, helped create the conditions for change. In addition to demanding respect for the international rules, urging regulation of the arms trade and holding perpetrators accountable, global civil society and international institutions must respond quickly when opportunities arise.

In Syria, as in so many conflict settings, civil society played a key role in providing vital support on the ground, documenting human rights violations and advocating for international assistance, and paid a high price for doing so. Now Syrian civil society must be enabled and supported in building an inclusive, just and democratic peace where human rights are respected. There’s no path to sustainable peace, in Syria and in the world’s many other conflict zones, that doesn’t involve civil society.